NOT ANOTHER PRETTY PICTURE

An increasing number of artists are turning away from traditional muralism towards holistic urban interventions that go beyond purely aesthetic or decorative purposes. Transcending traditional aesthetics, their work often serves as a platform for social and political commentary, inviting us to look beyond the surface to consider underlying messages, and thus also challenging us to think about the lasting effects and implications of muralism.

While traditional muralism brings light and color into an area, how can artworks on walls go further to explore deeper themes, social issues, and philosophical questions, and make political commentary?

One approach is through interactive and participatory projects that invite the community to engage directly with public art. These projects foster a deeper connection between the artwork and its audience, transforming passive observers into active participants. By involving the community, artists draw attention to social issues, lending relevance to their work and giving participants a sense of ownership.

Introduction

You’ve probably already noticed that many artists are turning away from traditional muralism. They go a step further, interacting directly in the urban space and creating urban interventions. But what exactly does that mean?

Imagine you are walking through your neighborhood and stumble across a work of art that is more than just a beautiful mural. It speaks to you directly, perhaps even with a political message or an unexpected question. In this way, it invites you to participate, and this is exactly what urban interventions are aiming for. It’s all about real engagement and debate.

In this chapter, you will learn how artists involve the residents of a neighborhood through interactive and participatory projects. They encourage people to become active, to put more thought into the world around them, and to help shape it. Instead of standing aside and watching, people become part of the process. This type of art creates a deeper connection between the artworks and us, their audience. Through urban interventions such as these, doors are opened to new experiences that allow us to see our surroundings with different eyes.

Jazoo Yang

Mixed media artist Jazoo Yang pursues her very own approach to urban art. She often creates site-specific installations using found materials, reflecting the layers of history embedded in urban spaces.

Yang was born in South Korea in 1979, and right from the beginning of her career, she was off to an original start, spending her weekends on unsupervised construction sites, where she painted the walls of half-demolished buildings and listened to the stories of former residents. In fact, the personal stories she heard of displacement and change had a profound influence on her art.

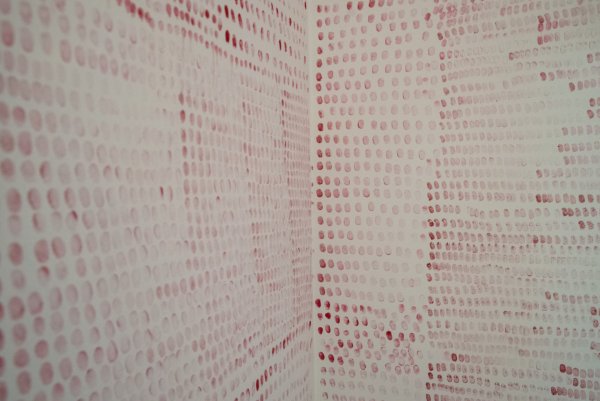

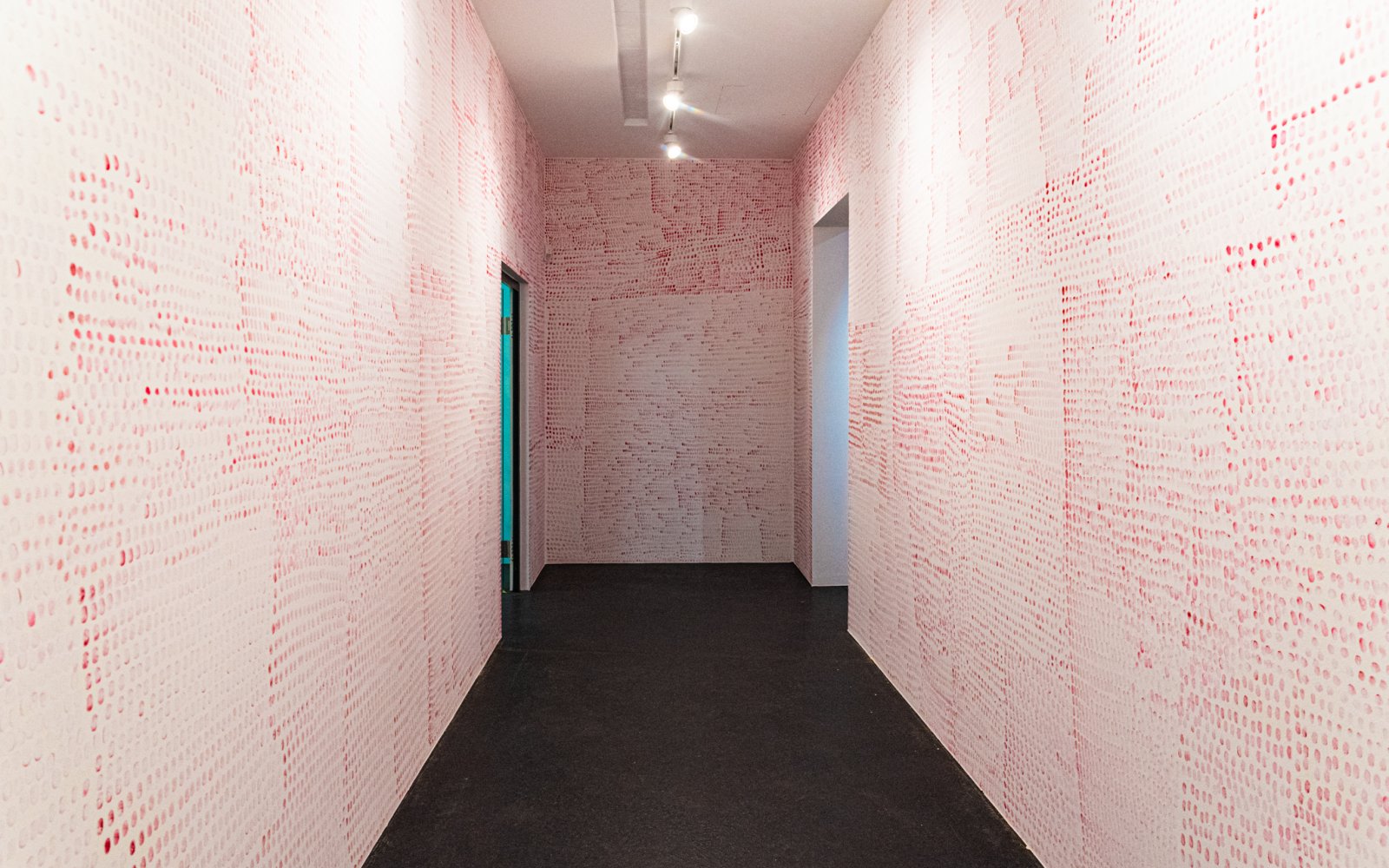

Later, Yang decided to cover an abandoned house with her thumbprints. This was the beginning of her Dots series, which gained her international fame. Perhaps you're wondering what makes it so special? Well, in Korea, the thumbprint, the “Jijang,” has enormous significance: like a signature, it can seal the sale of a house or its demolition. Yang translates this symbolic power into her art by placing thumbprints on abandoned structures to call the ongoing changes in the city into question.

Here in the exhibition, you can see an impressive work from her Dots series, which was created in the museum as part of a collaborative project. Yang invited senior citizens, all members of the local “Omabunker” (“Grandma Bunker”) group living in a home at Frobenstraße 94 in Berlin, to join her in placing thumbprints on the museum walls. In the course of the project, there were plenty of opportunities to get to know the participants’ life stories and to talk about their current concerns. The expansive community mural made up of densely arranged thumbprints serves as a quiet reminder of moments like these when people come together.

Painting Dhaka Project

In Lukas Zeilinger’s work you can experience the power of art as a social force. You will find it inspirational to see how art and collaboration can foster positive change. His projects create a strong community spirit and self-empowerment.

His participatory project Painting Dhaka took him to the capital of Bangladesh. There the artist and filmmaker taught graffiti art in the poorest neighborhoods, helping children find ways to express themselves and gain visibility. In the course of this work, graffiti proved to be an important tool for self-empowerment, and Zeilinger was deeply touched by his collaboration with the young people in his project.

What was at first only an art project developed into something more, as he tells us: “The more I spent time with the children, the deeper our bond became. It was a friendship that filled me with great joy and deep sadness. I couldn’t help but take a closer look behind the façade of a country and its capital that had been completely foreign to me shortly before.” This experience gave rise to the documentary Painting Dhaka, a film about hopelessness— and about overcoming it with the help of art. In this exhibition you can see a documentation from this impressive project.

Lukas Zeilinger’s ONE WALL, also known as Local Legends: Spandau – A Painting Dhaka Project is also a collaborative project and requires a short trip to Blasewitzer Ring 12 in Berlin-Spandau. There, the façade of a parking garage features an artwork by Zeilinger, created specially for the chapter LOVE LETTERS IN THE CITY. The design was developed in collaboration with young people from the Outreach B18 youth club, and aimed to accommodate their social perspectives. The cultural influence of graffiti encourages collaboration, mutual respect and a stronger sense of solidarity among community members.

INFORMATION

The photographs presented on site of the ONE WALL and C-WALL mural Local Legends: Spandau document the radiation of the exhibition into the city and are part of the chapter LOVE LETTERS IN THE CITY.

PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

"SPACE HACKING"

NEXT CHAPTER:

"DE-CONSTRUCT TO CONSTRUCT"